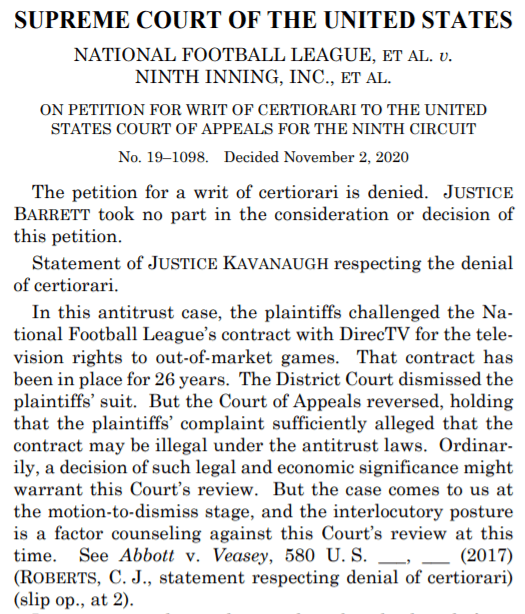

Yesterday, D’Juan Epps, apparently a fundraiser for Vanderbilt’s official student-athlete name, image, and likeness organization and an “associate director” within the university athletic department, filed a lawsuit seeking the recovery of unpaid fundraising commissions.

Epps’ suit, filed in the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia, names Student Athlete NIL LLC (“SANIL”) as the sole defendant and describes work performed in connection with Anchor Impact. According to a university website, Anchor Impact is “the official collective for Vanderbilt Athletics.” SANIL is a Delaware company registered to do business in Georgia, apparently a nationwide vendor assisting schools with the administration of their official NIL programs. SANIL’s principal office in Georgia appears to be a residence in Marietta associated with Susan Gout, a sports marketing professional. Records identify Gout, a Penn State alum, as SANIL’s registered agent.

An undated interview describes Epps as Anchor Impact’s “general manager,” and it quotes his description of Anchor Impact’s “join[ing] forces with [SANIL] in an initiative that will significantly impact the lives of Vanderbilt’s student-athletes. The world of college athletics is evolving, and this partnership will empower these young men and women to navigate the complexities of name, image and likeness opportunities while fostering their personal and professional growth.” Two years ago, Epps went on camera to discuss how Anchor Impact helped student-athletes partner with community nonprofit causes.

In his lawsuit, Epps alleges he raised about $3.5 million for Anchor Impact; that a contract between him and SANIL entitled him to uncapped commissions on that amount; and that SANIL did not pay him his full commission. He further alleges that, while he is a resident of Murfreesboro, business transactions relevant to his case occurred in Georgia. Records indicate that SANIL has not yet been served with or appeared in the lawsuit.

Vanderbilt athletic recruiting was in the legal news last year, when breakout star transfer quarterback Diego Pavia scored a preliminary court victory allowing him another year of eligibility with the Commodores in 2025. While the NCAA seemingly acquiesced to the ruling, voluntarily extending its effect to other, similarly situated student-athletes, it later appealed, seeking reversal. That appeal remains pending.

The potential consequences of the dispute between Epps and SANIL would seem to be narrower than those of Pavia’s case, but we still will keep an eye on it.

_______________________________________________________________

Previously

Foreign College Basketball Stars Are Missing Out on Endorsement Money Due to Visa Rules (via Reason)

The NCAA’s response to Georgia’s new NIL law reveals the emperor’s new clothes