[The following is an introduction to a more thorough study I intend to publish at Banished to the Pen following the conclusion of the current MLB season the purpose of which is to suggest an approach to harmonizing traditional ways of thinking about the sport’s annual MVP award with available sabermetric principles. -ed.]

Last week’s Zach Britton trade reminded me about the idea of championship win probability added (cWPA). In 2016, Ben Lindbergh made the case that Britton, then serving as the closer for the Baltimore Orioles, should win the award for the most valuable player in the American League based on the idea that Britton, at least during the regular season, had done more to help his team win the World Series than any other player had helped his own team win the championship. Britton– again, a relief pitcher who threw sixty-seven innings– finished eleventh in MVP voting. Mike Trout, the WAR leader, claimed the award, his second, and I don’t suspect many people have thought much about cWPA since then.

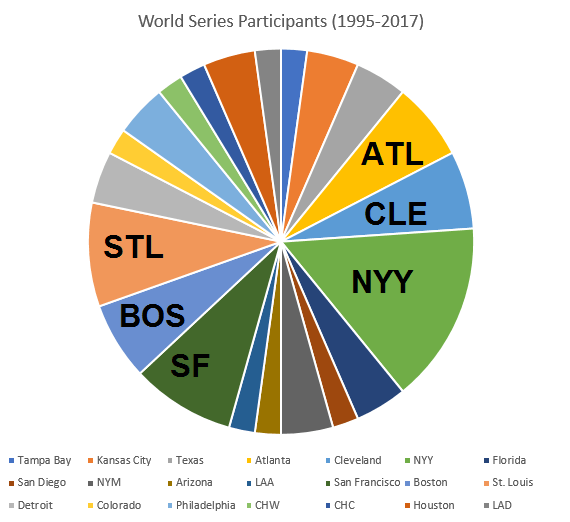

What should make cWPA (defined: cWPA “takes individual game win probability added (WPA) and increases the scope from winning a game to winning the World Series. Where a player’s WPA is the number of percentage points that player increased or decreased their team’s probability of winning a single game, their cWPA is the number of percentage points the player increased or decreased their team’s chances of winning the World Series.”) attractive to a broad swath of the MVP electorate is that it accounts for the traditional notion that the individual award-winner ought to have been on a winning team. When handing out performance awards for a given season, it makes sense to reward players based on what they actually accomplished, as opposed to what they should have accomplished but for bad luck, sequencing, weak teammates, strong opponents, environmental variations, and other contextual and extrinsic factors. After all, these factors work, to some extent, on all players, and just as we determine team season standings based on actual win percentage (and not a sabermetrically adjusted winning percentage), so too should we determine individual season awards based on actual results.

This is not to say that the MVP should go to the player with the best batting average or the Cy Young to the hurler with the most pitcher wins, obviously. While using cWPA as a guide will steer us toward players who are, in the conventional sense, winners, it uses accepted sabermetric principles to maneuver in that direction. Still, I think there may be some concern that cWPA, when used alone as a player-valuation measure, might be too context-dependent and inclined to reward disproportionately an otherwise unremarkable player who happened to find himself in one or two of the right places at one or two of the right times. Certainly, though, it seems likely that a player who accumulated performances in those situations often enough to find himself near the top of the cWPA leaderboard also would be a well-rounded and highly productive player in all situations.

Still, I was curious how well cWPA correlated with WAR, something it ought to do reasonably well if it’s to be available as a useful informant for MVP voters. I pulled the cWPA numbers for the current season and used FanGraphs’ version of WAR mainly because their combined WAR leaderboard made data manipulation easier.

(click image to enlarge)

I don’t have a statistics background, so I won’t comment on the significance of the correlation between cWPA and fWAR except to say that it seems sufficiently strong. If you’re curious about who’s who on this plot, here are the current top-ten players by cWPA:

There is a lot of significant, championship-relevant baseball yet to be played in 2018, and a more significant study of the above would have involved prior, completed seasons, but I think there’s something here and wanted to share what I had compiled on the current season as it moves into August and teams begin their playoff charges in earnest. I anticipate updating this information after the conclusion of the regular season and supplementing it with historical data to create an even more robust analysis. In the meantime, I welcome any input on win probability added and seasonal awards.