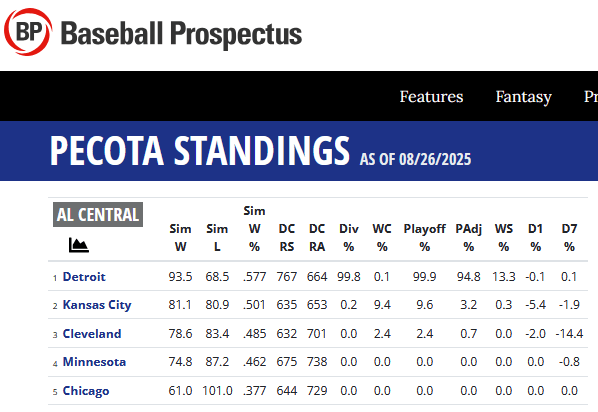

What is this nonsense? Last week, Baseball Prospectus’ PECOTA declared it a one-hundred-percent certainty that the Detroit Tigers would appear in the 2025 MLB playoffs. Today, though, the ostensible gold standard in baseball-projection machines has engaged in a very unfortunate bit of retrenchment:

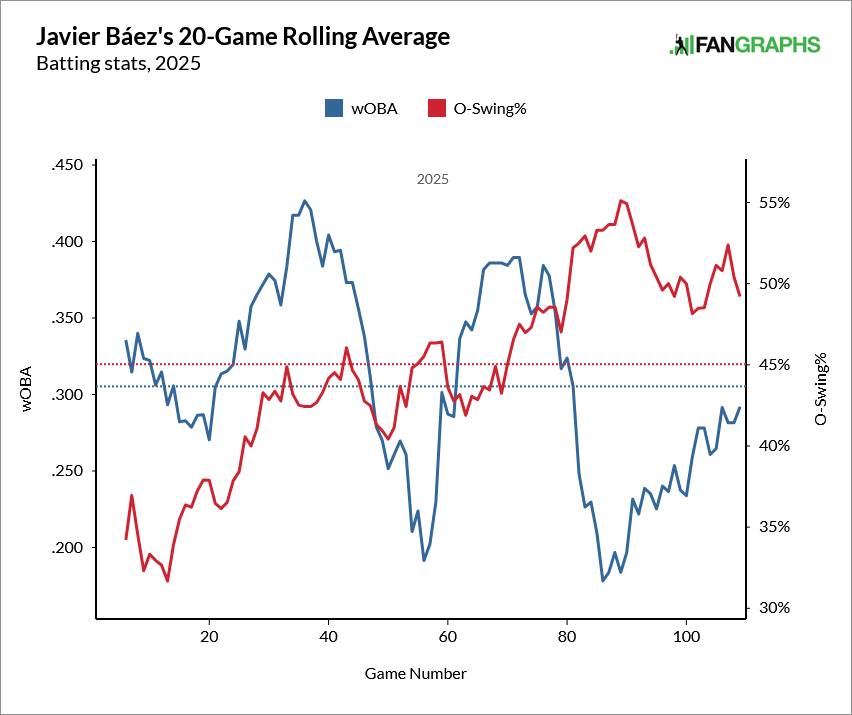

To be sure, I would not blame anybody for downgrading Detroit after Tarik Skubal surrendered a grand slam during a five-run seventh inning that ignominiously crowned a Tigers loss last night to a vagrant team playing in a minor-league park. Far from the August heater the team generated to fuel their run to the 2024 postseason, however, these Tigers have struggled in the second half with the likes of the Twins, Pirates, and A’s in a manner belying a true talent level perhaps somewhere below their overall winning percentage. And Javy Baez doing that bad thing again feels like a microcosm of team-wide regression trends in action:

But BP’s PECOTA conceded none of that reasonable skepticism. It said this final outcome was a guaranteed certainty; no hedge, error margin, or other reservation of any kind. Presumably, it knew that Skubal could have a bad night, Baez could turn back into a pumpkin, and Jack Flaherty could continue to melt down, but it said it was not concerned. Having crossed that triple-digit threshold of certitude, it probably did not love what it saw in Sacramento last night, but one envisioned PECOTA taking that on the chin with an unwavering forward stare into a known and unavoidable future.

In short, once you go to 100%, you simply cannot go back. Again a concession from me: I will grant force majeure: If the season suddenly and prematurely ended due to a public-health catastrophe, war, or series of natural or Manfred-made disasters, then PECOTA probably gets a pass. Short of that, though? If 100% means Fool me once, shame on you. But fool me twice, baseball robot? My promise to the ALDLAND readers is that I will not be fooled again.

___________________________________________________________________

Previously

Death, Taxes, and the Detroit Tigers in the 2025 MLB playoffs?

More Likely Than Not: The 2025 Detroit Tigers are winning, and winning matters

Maximum Tork: How Spencer Torkelson is cranking up his hot start in 2025

Before you accuse me, take a look at Jake Rogers

Is it Tiger Time? Tarik Skubal says so